Zoom Accounts For Sale on the Darknet Highlight On-Going Need for Better OPSEC

As most of the world shelters in place due to the COVID-19 pandemic, Zoom – the video conferencing tool we’re all very familiar with by now – has witnessed an extraordinary surge in use. Employees are on calls in Zoom for hours a day conducting meetings with their coworkers. Families and friends, unable to meet in person, connect on Zoom for virtual happy hours, weekends and holidays. In the first quarter of 2020, Zoom Video Communications added 2.22 million monthly active users, contributing to what is rapidly approaching a total of 13 million monthly users.

Given the fact hackers were and have also been on lockdown in their homes, it is no surprise that less than a month after most of the U.S. went under quarantine, compromised Zoom accounts appeared for sale on criminal forums in the deep web and darknet. In late March, news headlines declaring that there has “Zoom Breach” quickly began appearing en masse. As a result, we decided to take a closer look at what we’re calling the “Zoom Situation” (more on that below), and in this blog will outline how in a matter of months, this convenient, free video conferencing software became a major public information security concern.

One item that we want to note upfront is that Zoom – as in, the company – was not breached. To our knowledge, no hacker gained access to their user database or broke into their servers in any way. As analysts, we take care to differentiate between “breaches,” “leaks,” “credential compilations,” etc., because they mean very different things in relation to the cybersecurity posture of the targeted organization.

Zoom is only as insecure as your password reuse habits

The latest offers for Zoom accounts across darknet forums and marketplaces speak less to the security of Zoom’s software and more to the continued reuse of usernames and password combinations across commercial applications. In other words, the greatest and most important takeaway from this situation is that it would have been entirely avoided if Zoom users weren’t reusing passwords they’ve used elsewhere.

There’s nothing particularly special about Zoom’s conferencing security. The platform itself relies on the standard transport layer security (TLS) 1.2 protocol, which replaced the depreciated Secure Sockets Layer (SSL) over HTTPS, and encrypts chats using the Advanced Encryption Standard (AES) 256-bit block cipher. However, in spite of this fairly basic framework, there is no indication that the 500K accounts offered for sale were collected from exploiting a vulnerability within the Zoom application.

Instead, DarkOwl assesses with high confidence that the hackers selling this data have instead used a method called “credential stuffing” to test Zoom login authentication against publicly available username and password combinations. So, if your email address and password were exposed in another breach, even from years back, and you used that same email/password to log into Zoom, you would now be a part of what others are referring to as the Zoom Breach.

By running old, leaked credentials through a credential-stuffing validation tool, hackers managed to find and confirm the logins for 3.8% of Zoom’s registered members in historical data breaches. Anyone using a tool like this could target any organization they wanted to.

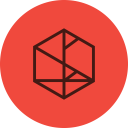

One such tool called SNIPR (pictured) is a leading credential-stuffing toolkit supporting multiple attack surfaces including web requests (http/s) and IMAP-based email accounts without the need for any command-line or shell programming from the user.

Figure 1: SNIPR credenial-stuffing toolkit in action (Source: www.snipr.gg)

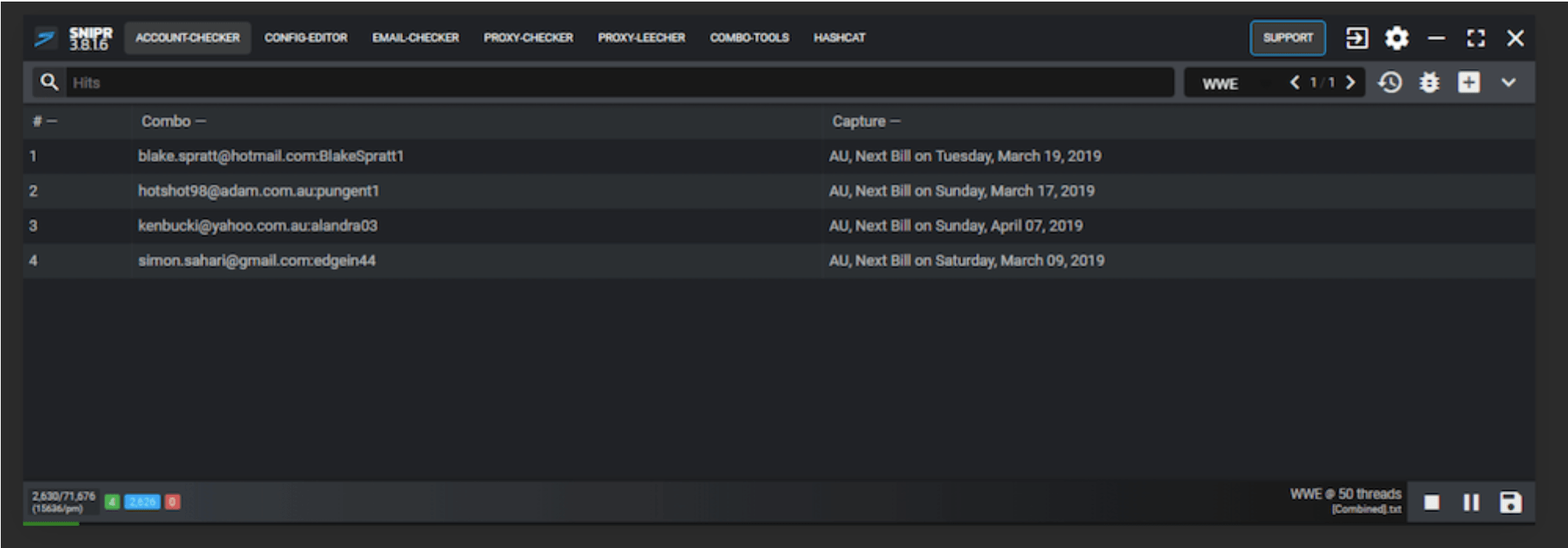

Because of the increased worldwide use of Zoom due to the pandemic, Zoom became a target of interest for (presumably) bored hackers, resulting in a list of 500K verified Zoom accounts being offered for sale on the darknet service, POPBUY Market for 10,000 USD in BTC ($50 USD per account). It is unclear from the vendor’s listing on the market who is behind the offer or if it is legitimate.

Figure 2: POPBUY Market (Source: Tor Anonymous Network, Captured Live 21 April 2020)

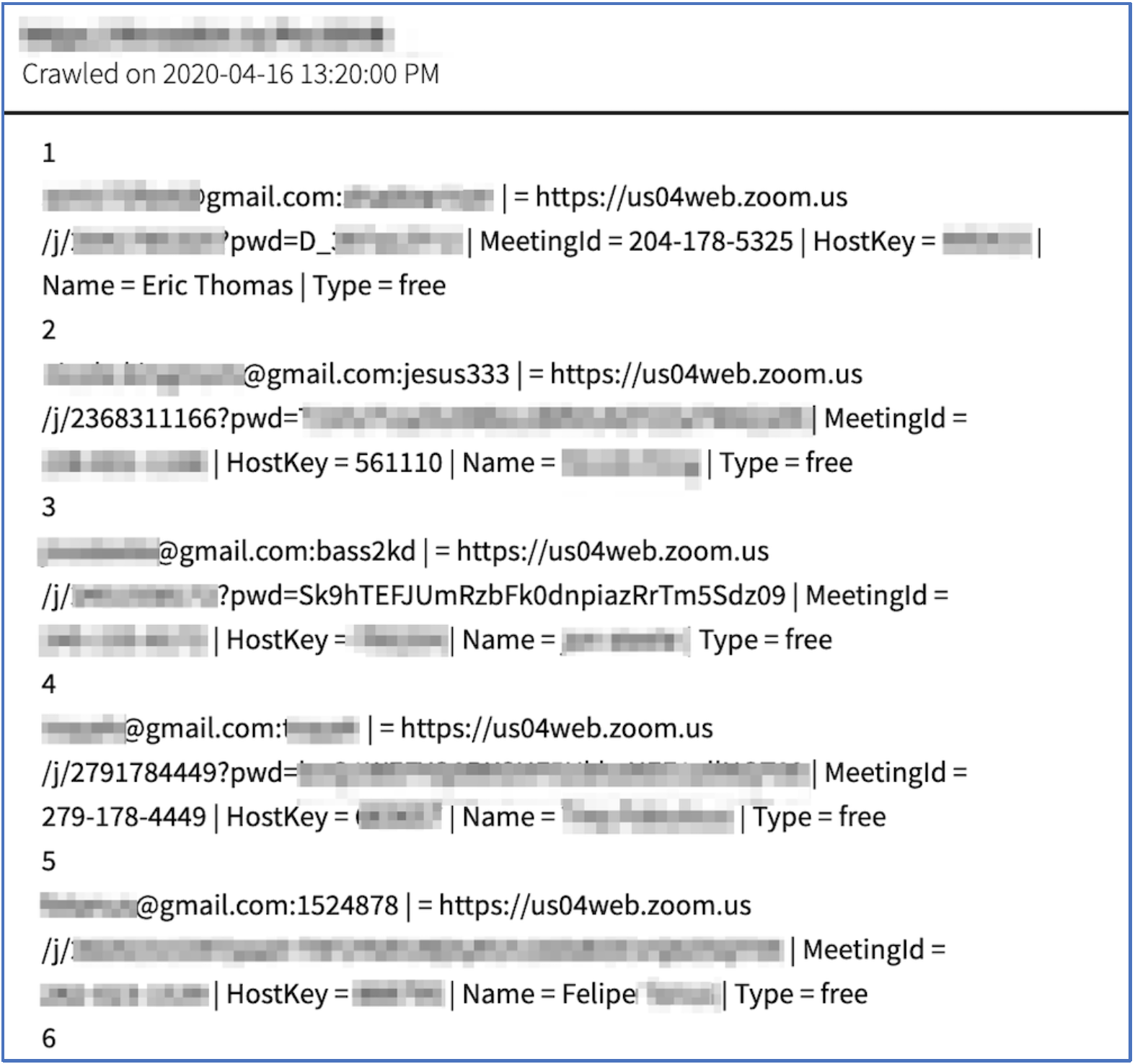

Figure 3: Sanitized Snapshot of Sample Zoom Data offered for Sale (Source: DarkOwl Vision MD5edf8ca26843157d313f6502ff970a9bb)

Another listing for Zoom account data appeared on deep web hacking forum, nulled.to, at a much cheaper price than the darknet marketplace above. This advertisement pointed to the hacker’s “Shoppy” account that offers each account for as little as 0.25 USD and included an external link to a sample file with some of the compromised data. The paste included 91 records with the username, password, Zoom URL (with password), Numerical HostKey, Real Name of User, and account type.

Our analysts confirmed the sample “hacked accounts” in the offer include email address and password combinations indexed in Vision from previous data breach collections confirming the hackers likely verified the accounts using credential stuffing.

DarkOwl assesses the significantly reduced price to the darknet market is the result of Zoom advising users to change their passwords and the account data being virtually useless to the buyer.

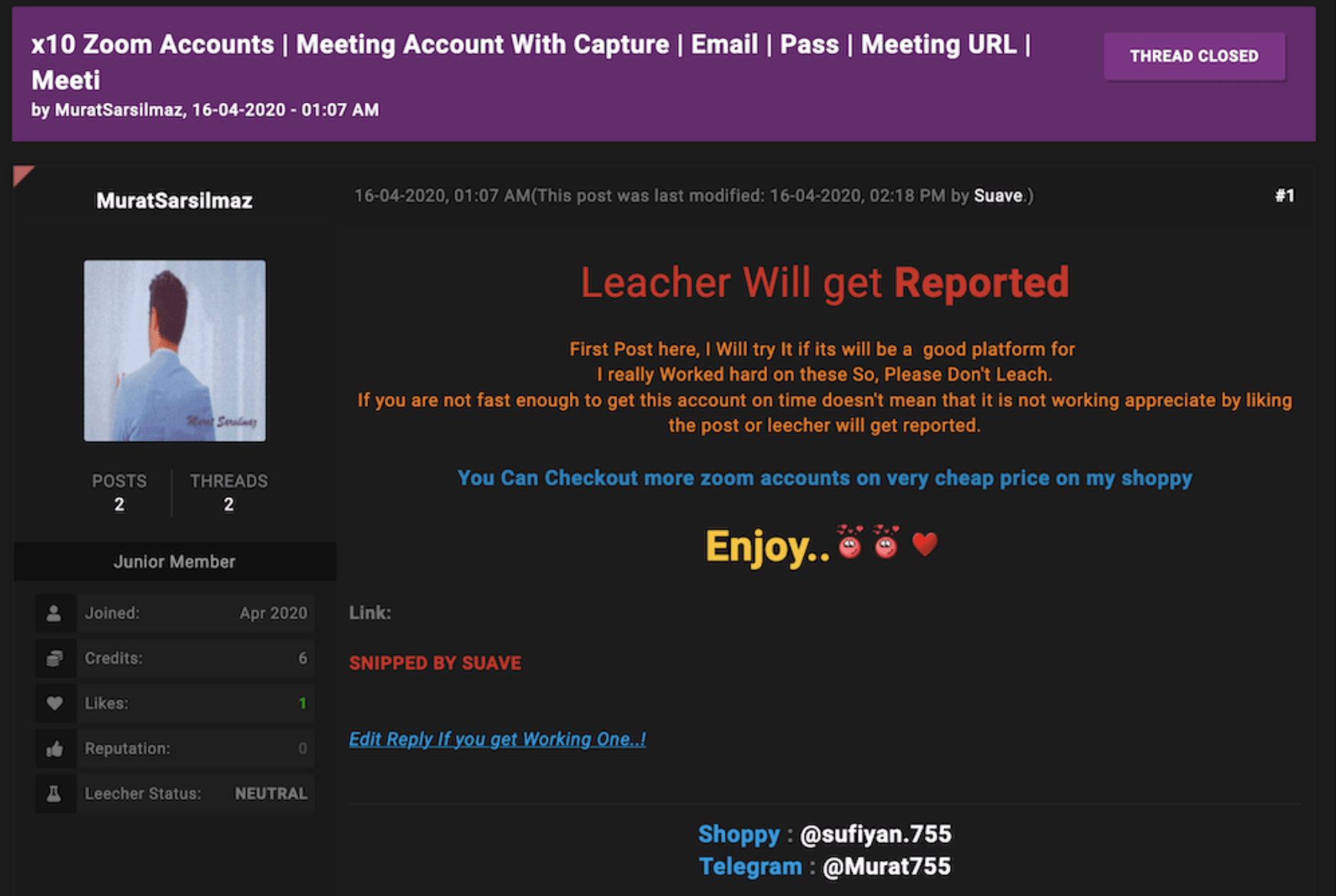

The monikers used by the hacker offering these accounts is sufiyan.755 and MuratSarsilmaz. This moniker has “junior member” status on Surface Web forum, LeakZone and no darknet documents in DarkOwl Vision.

The hacker’s Shoppy account also lists very few other offerings, suggesting this is a beginner hacker entering the market.

Figure 4: Offer for x10 Zoom Accounts (Source: LeakZone.net Deep Web Forum, Captured Live 21 April 2020)

Zoom may be in the clear in this case, but historically does not seem concerned about user privacy

Zoom is sharing your data with Facebook

In March 2020, open source reporting confirmed that Zoom has been making money by sharing personal user data with Facebook in return for subsequent advertisement revenue. A new, resulting lawsuit states that Zoom, “failed to properly safeguard personal information” of its users. The lawsuit follows a MotherBoard report that verified how the Zoom iOS app for Apple smartphones was sharing information with Facebook about its users without their consent.

Data that Zoom shared with Facebook included:

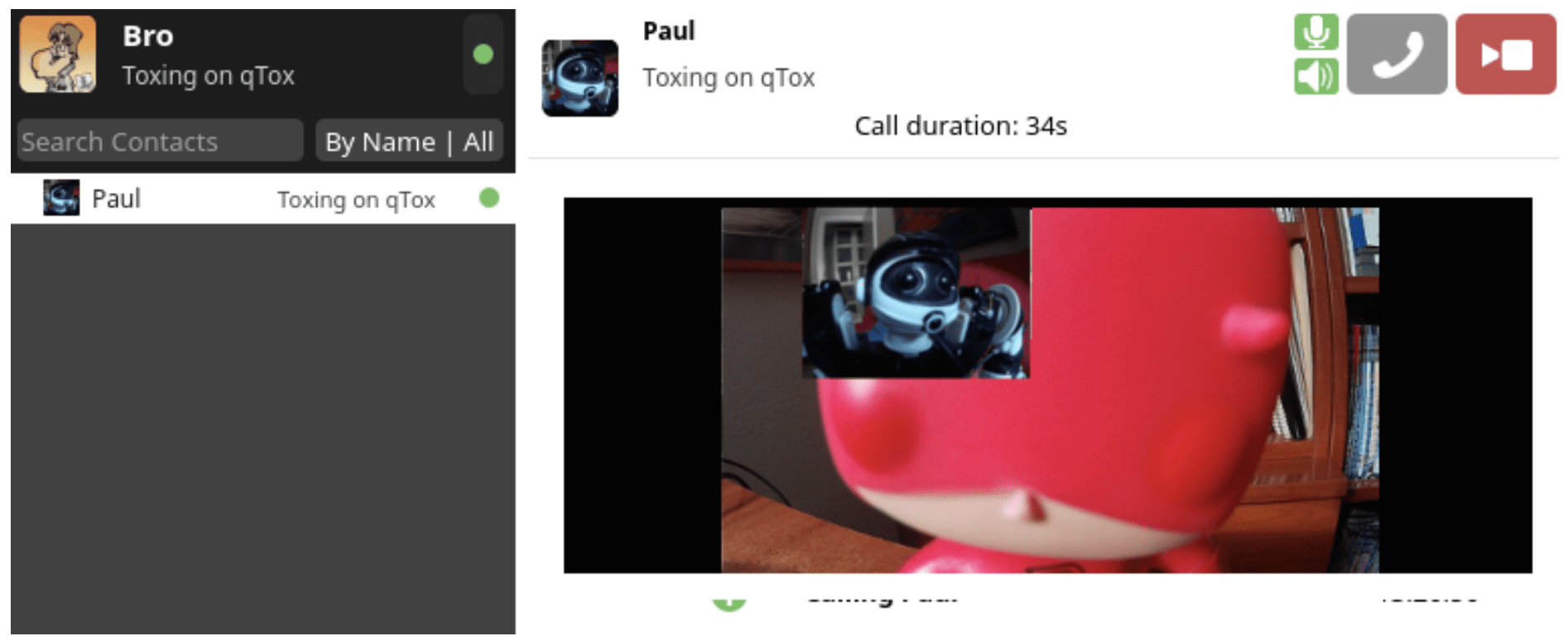

Figure 5: qTox, an alternative to Zoom, supports encrypted video conferencing (Source: http://www.linux.com)

-

a flag when the user opens the app,

-

details on the user’s device such as the model

-

the time zone and city they are connecting from

-

the phone carrier they are using

-

a unique advertiser identifier created by the user’s device which companies can use to target a user with advertisements in the future.

This sharing of data with Facebook was not included in the application’s Terms and Conditions, which is the foundation for the lawsuit. Most anonymous and privacy conscious internet users avoid video conferencing software like Zoom and prefer encrypted applications like qTox (pictured) or Signal, or will simply forgo video chatting all together.

They’ve allowed Zoom-bombing to thrive

The science of Zoom-bombing is as simple as BASH. Before the pandemic, some Zoom users complained of random people connecting to their Zoom conference meeting rooms without saying anything. Other hosts even received Zoom’s alert email “participants are waiting” at all hours of the night, which appears to have been reconnaissance for testing what has morphed into the pandemic Zoom-bomb.

Since quarantine, many conferences have been subjected to the Zoom-bomb where hackers enter the conference then subject the unwilling participants to an array of shocking and often illegal content. The frequency of this has resulted in now widespread use of password protected conferences and hosts approval required for participants entering after the meeting has started.

How does this happen? Largely, this can be attributed to Zoom’s overly simple URL identifier for meetings connects an array of 9 numbers at the end of the address to the user’s meeting identification: https://zoom.us/j/<string of 9 random numbers>. DarkOwl analysts shared that this simple string of 11-numbers could be auto-generated in a loop inside a BASH shell script or any popular scripting language that then tests the URL with the UNIX curl or wget command. Confirmed accounts could then be targeted by manually “bombing” the conference call with malicious audio and imagery.

Some open source reports suggest that many of the trolls behind the majority of the Zoom-bombings are anti-semitic hackers targeting Jews during online meetings by flooding conferences with imagery of swastikas and Nazi soldiers. There’s a lot of evidence that suggests that is true, however a number of hackers have targeted many other non-faith-based and academic conferences, as well as individuals.

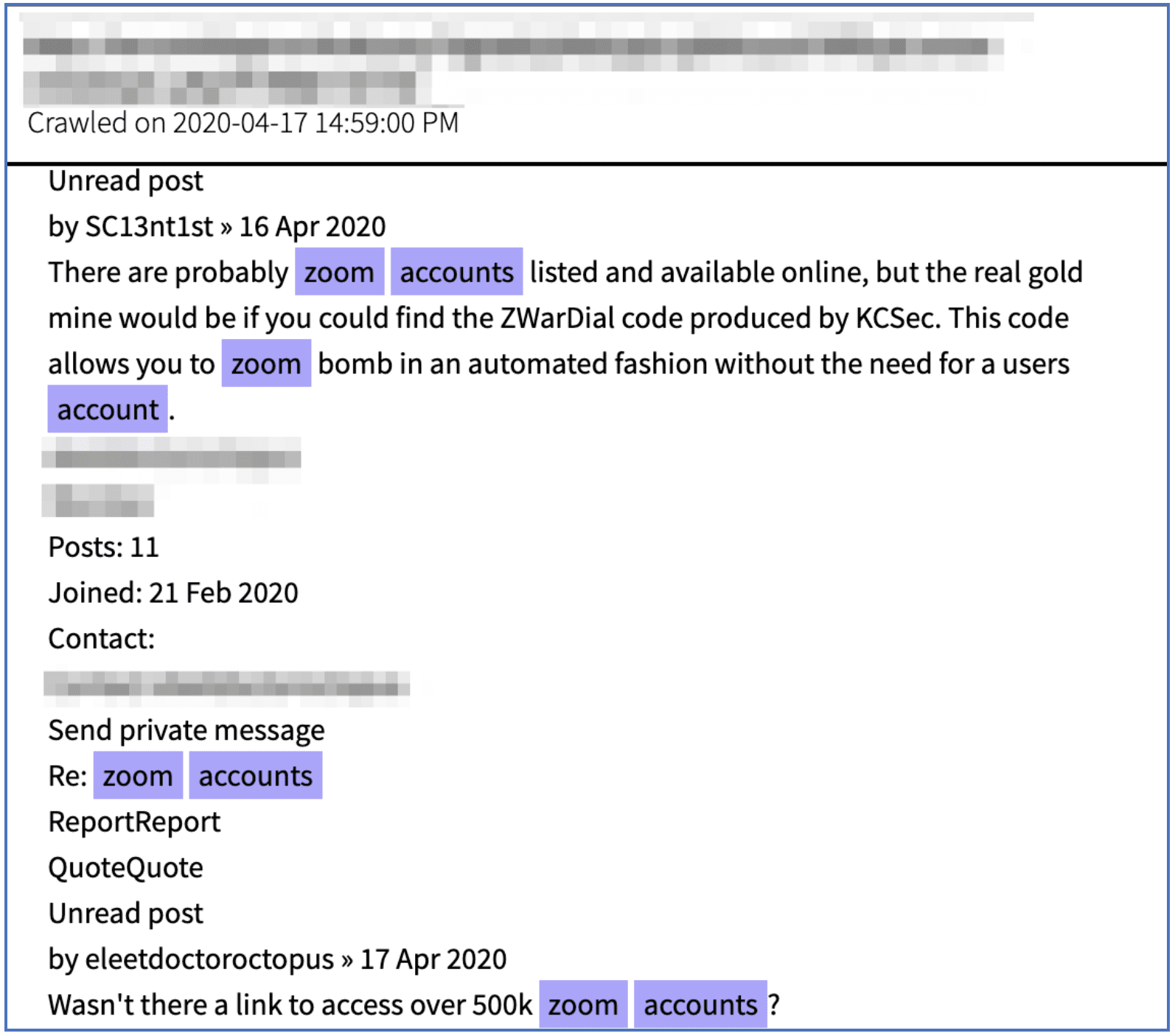

To make the situation more complicated, adding passwords requirements to Zoom meetings soon might not be enough – though we do strongly recommend this as an initial step. For example, last week, hackers on popular darknet cybersecurity forum Torum mentioned a resourceful tool called the ZWarDial code, developed by KCSec. According to Brian Krebs, this code apparently leverages the BASH script idea and automates the Zoom-bomb without need for the user account or password. This intelligence suggests that hackers are already evolving their tactics and techniques to Zoom’s security implementation.

Figure: 6 Hackers discuss sophisticated tools that could circumvent Zoom security (Source: DarkOwl Vision MD5: 5ddbbce8549cc1b33628dc0eba5b8280)

Hackers might be attempting to disable Zoom accounts in the future

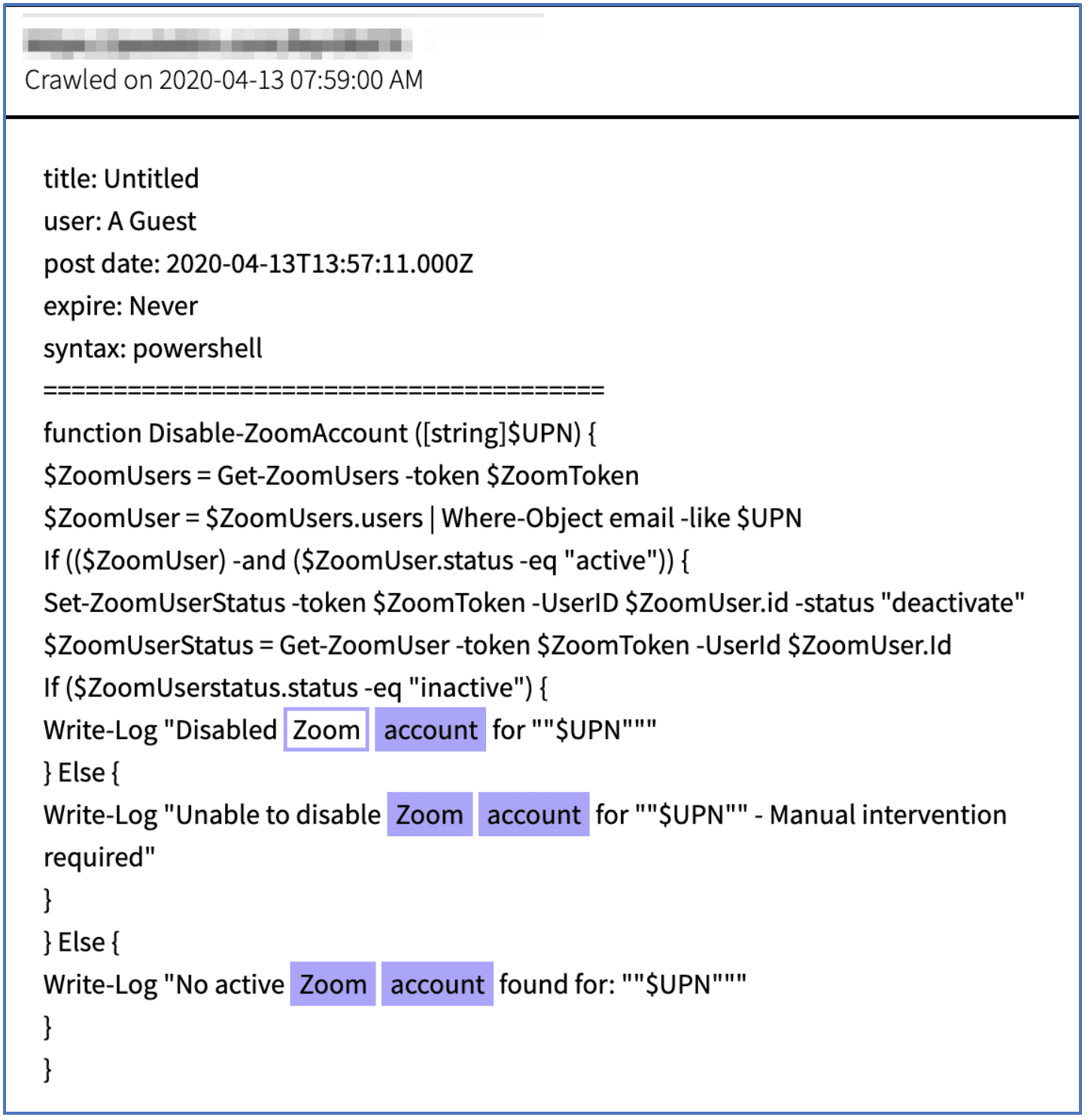

DarkOwl Vision also captured a snippet of Powershell source code for a function called “Disable-ZoomAccount” which includes logic to check if a user exists on Zoom, via a User Principle Name (UPN), in this case an email address, and if the legitimate user is “active” then the source code changes the ZoomUserStatus to “deactivate.” The function writes to a log if it was successful or if manual intervention is required for disabling the account before closing. The purpose of the function or how it will be used in the wild was not identified in the deep web document.

Figure 7: Powershell source code for a function that disables Zoom Accounts (Source: DarkOwl Vision MD5: 28e89b4454f2dfdbc5a97fb0b2c1c92c)

Zoom is rapidly patching security issues

Zoom has responded quickly to criticism of their video conferencing platform. This is perhaps in response to the fact that in late March and early April 2020, New York City school districts – as well as Elon Musk’s Space X operation – publicly stated they would no longer be using Zoom software due to ongoing security concerns.

The digital conferencing platform has also responded with an in-depth security audit and released multiple security updates to the software. Security updates include support for more complex password requirements for meeting passwords, the random meeting identification has increased from 9 digits to 11, and password protection for shared cloud recordings of meetings is on by default.

To prevent unauthorized and un-attributable malicious access, there is no longer the option to “Join Before Host” and all participants require a Zoom account to participate in a Zoom conference call. Zoom had also temporarily disabled third-party support for file-sharing services such as Box and OneDrive; as of late last week’s security updates, this feature was available again.

Takeaways and advice

When it comes to Zoom, there are still steps that you can take right now to add an additional measure of security to yourself and your organization:

-

What happened with Zoom could happen with any internet-based application. So, remind your employees, family and friends to chose unique passwords and email address combinations on every commercial application.

-

Adding password protection to Zoom meetings is the first step to mitigating unauthorized access to the user’s conference room.

We can’t emphasize this enough: what happened to Zoom (and Zoom-users) can happen to any internet-based application at any time. It only takes one hacker with access to old, breached/leaked credential data and a credential-stuffing tool to target an organization of their choosing. As such, with the current level of dependency on remote working and virtual video conferences, DarkOwl encourages all to be vigilant while using any platforms that require user account registration:

-

Set-up accounts on such software with unique (if not disposable) email addresses, using complex passwords not used anywhere else

-

Apply any and all additional security options available, such as password-protection for the meeting and limiting access to stored shared recorded meetings.

If you are considering abandoning Zoom altogether, TechRepublic recently posted a list of alternative video conferencing applications.

Thanks for reading our blog! Contact us if you want to know more about this issue or discuss how DarkOwl can help mitigate your account information appearing on the darknet.

Explore the Products

See why DarkOwl is the Leader in Darknet Data

Products

Services

Use Cases