What Does a Real Cyberwar Look Like?

August 03, 2022

On the 24th of February, after months of failed diplomacy, war broke out between Ukraine and Russia. While the war was being fought in the physical realm, Ukraine’s Ministry of Digital Transformation turned to the digital realm for assistance. Within days of the invasion, a call across underground forums and chatrooms was placed and hundreds of thousands of hacktivist volunteers answered.

Ukraine’s call for help sparked off the first ever global cyberwar which for the first time in history has been waged between two countries simultaneously with a land war. This webinar looks at what we have learned from the cyberwar to date.

For those that would rather read the presentation, we have transcribed it below.

NOTE: Some content has been edited for length and clarity.

Kathy: Hi, everyone. Thank you for joining today’s webinar, “What a Real Cyberwar Looks Like.” My name is Kathy. Dustin and I will be your hosts for today’s webinar…. and now I’d like to turn it over to our speaker for today, Mark Turnage, our CEO here at DarkOwl, to introduce himself and begin.

Mark: Thank you very much… it’s a lot more fun for me as a presenter to answer questions as we go along, and so I would very much love it if you have questions, put them in the chat and Kathy or Dustin will interrupt me and we can have a conversation instead of a one way webinar.

We at DarkOwl have covered the Ukraine-Russia conflict extensively since it began in February, and even a little bit before that. Many of you may have seen our posts and our blog covering the war. We thought it would be useful to circle back and give an update and some of our observations on the impact of the war on cyberwarfare theory and practice.

There are just four areas of this webinar that I want to cover today. One is I want to talk a little bit about what the competing theories of cyberwarfare are, because those competing theories inform some of our observations on how the actual war, which is the first war between two nation-states, first extended cyberwar between two nation-states, has unfolded. And then I want to talk about some of the impacts on the internet and on the concept of modern warfare. And then we’ll make some concluding remarks. So, roughly, the slides that I’m going to walk through and hopefully the conversation we’re going to have follows this agenda.

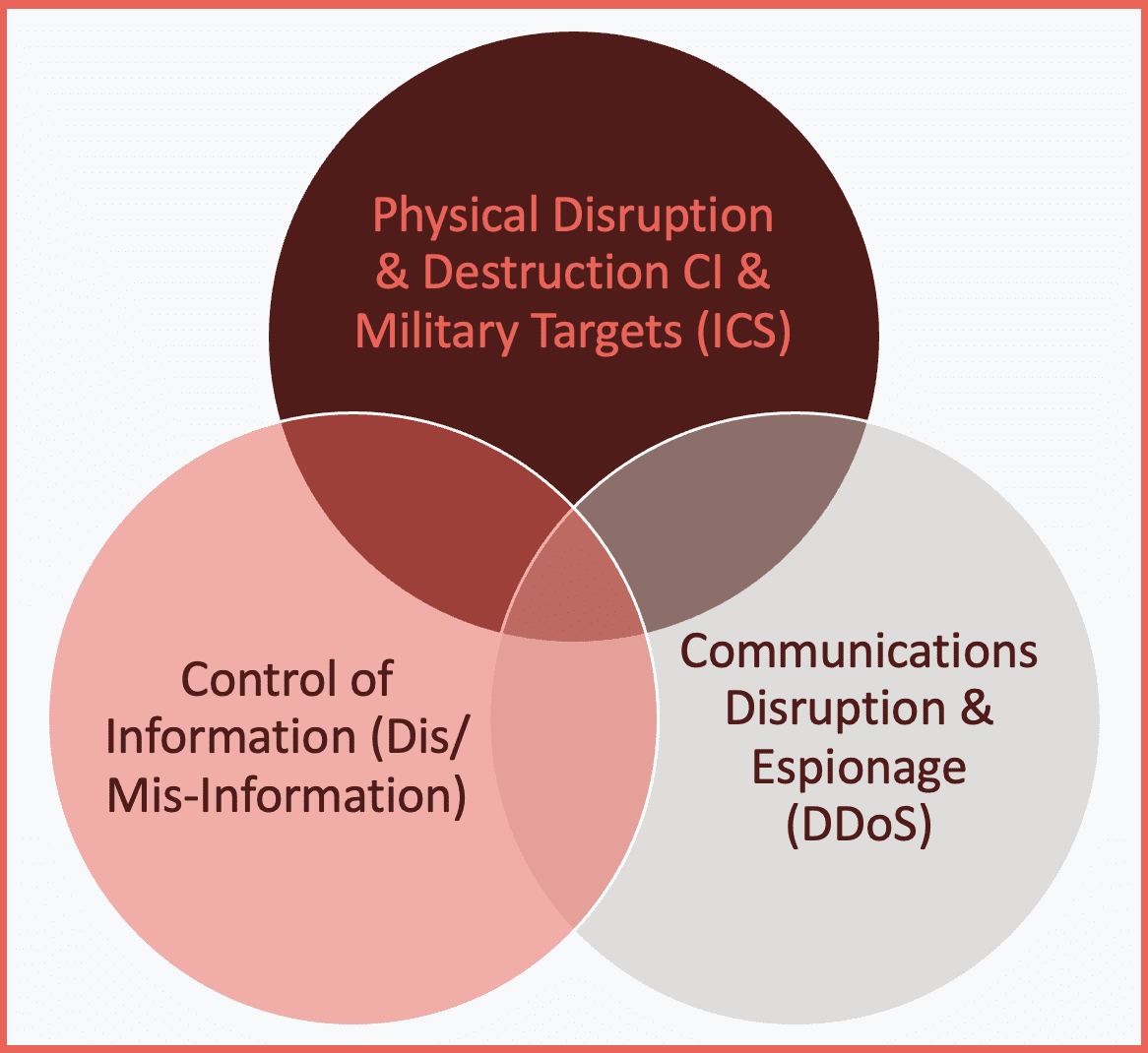

One of the problems with cyberwarfare in general is that it suffers from pretty significant definitional ambiguity, by which I mean, if you talk to people, people have very different views on what cyberwarfare actually is, and if you look at these three overlapping circles, the top being physical disruption, the lower left being misinformation and disinformation, and the lower right being sort of communications disruption and espionage, cyberwarfare actually touches on all three of those.

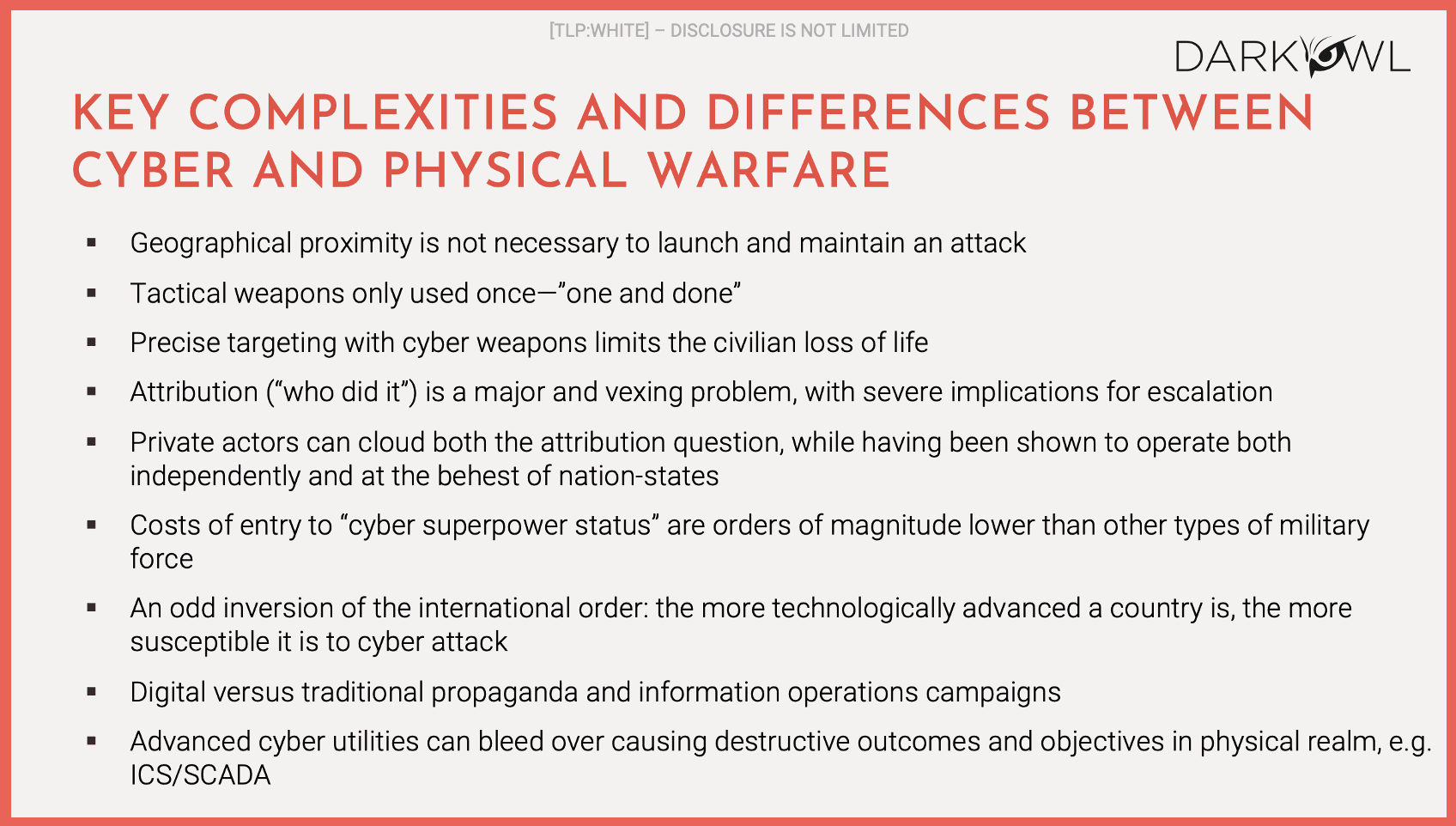

And so somewhere in the overlap between those three circles are the various definitions of cyberwarfare. And perhaps the best definition that I personally like is the one on the lower left in a cyber school called the Revolutionist: actions by a nation-state to penetrate another nation’s computer or networks for the person’s purpose of causing damage or disruption. Pretty straightforward. It speaks to a variety of degrees. It speaks to each of those three circles. But again, the point here is that there is no one definition of cyberwarfare. We can’t talk about cyberwarfare without understanding some of the complexities and some of the significant differences between cyberwarfare and physical warfare. And so, I want to spend a little bit of time on this slide because I think it’s fairly important as we talk about how the cyberwar between Russia and the Ukraine has unfolded.

One of the key differences between cyber and physical warfare is that geographical proximity is not necessarily launch and maintain an attack. Hypothetically, two countries on opposite sides of the globe could fight a cyberwar between the two of them and it could be quite a fierce war with significant collateral damage, and they wouldn’t be anywhere near each other. Another key difference is that the weapons that are used in cyberwarfare are largely one and done. Once you mount an attack on an electrical grid and it’s understood by the opponent how you’ve mounted that attack, they can patch that vulnerability or they can close that door that you walked through and you will not be able to walk through it again.

And so, one of the key differences here is that you can only use those weapons one time and that actually has an impact on how this particular war has been waged. One of the benefits of a cyberwar is that you can more precisely target cyber weapons. Anyone who’s followed the news can see that when either the party shell the other side and oftentimes civilians are killed because they’re in the neighborhood or they’re in the physical proximity of military weapons and there has been significant loss of life in this warfare. Cyber weapons have the ability to be more precisely targeted. It does not mean that there won’t be a civilian loss of life.

We’re going to talk about some explosions that have occurred in Russian oil and gas facilities that have in fact caused civilian loss of life. But the theory here, and it would appear to be born out by reality, is that civilian loss of life is nowhere near as much as in a physical war. A fourth key difference is that attribution of who did it is a major problem and it has really severe implications for escalation. If you don’t know who it is that has attacked your electrical grid or taken your internet offline and you can’t actually be certain of it, a potential retaliation against your enemy or against the enemy you’re fighting at the time might have an escalatory implication that isn’t deserved. So attribution in non-cyberwar times is difficult… in cyberwar that is even more complex because it has this escalatory component to it.

Private actors can cloud the attribution question. And the question is if a private actor jumps on board, for example, on behalf of the Ukraine and attacks Russia or tax targets in Russia, are they acting on the behalf of the Ukrainian government or are they acting as private actors who may be just hostile to Russia, and vice versa? Same thing for the Russian side. And that really clouds the question of who’s in control of this particular part of the war. So those first five bullet points, I think, are critical components to be considered in any evaluation of what cyberwar looks like and how it could be waged in the future.

There are a couple of other points I want to make which are quite interesting in the context of thinking about a cyberwar between two countries. Several years back we estimated that a nation-state could attain superpower status for less than the cost of an F16 jet on an annual basis, considerably less than the cost of an F16. So, the cost of entry to become a cyber superpower in today’s world are orders of magnitude lower than other types of military expenditures. And we’ll come onto a slide here that talks about who are the superpowers, but there are countries that punch well above their weight because they’ve made that investment in becoming either a superpower or near superpower.

One odd inversion of the international order, the more technologically advanced a country is, the more susceptible it is to a cyberattack. It goes without saying that North Korea, which is not heavily industrialized, not heavily complex from a technological perspective, oddly, is aspiring to cyber superpower status, is probably one of the least susceptible countries in the world to a cyberattack because it’s not connected. The grids are not connected. The level of complexity through the society is very low. On the other hand, both Russia and the United States and the Ukraine are heavily connected societies and are very susceptible to cyberattacks. The point I want to make is that there are some very significant differences between how cyberwar is waged and can be waged and what the implications of that are to how it’s waged, how physical warfare is waged.

I started off by talking about how there are many definitional ambiguities in cyberwar. This is how the popular press thinks about cyberwarfare. If you listen to CNN or Fox News or any of the cable TV stations, this largely captures how people think about a cyberwar; “With a nation in the dark, shivering in the cold, unable to get food at the market or cash at the ATM, with parts of our military suddenly impotent and the original flashpoint that started it all going badly, what will the Commander in Chief do?” (Clarke and Knake, 2012). That is the popular theory of cyberwar that once a cyberwar is launched, people will go back to the Stone Age. And that theory still permeates popular culture.

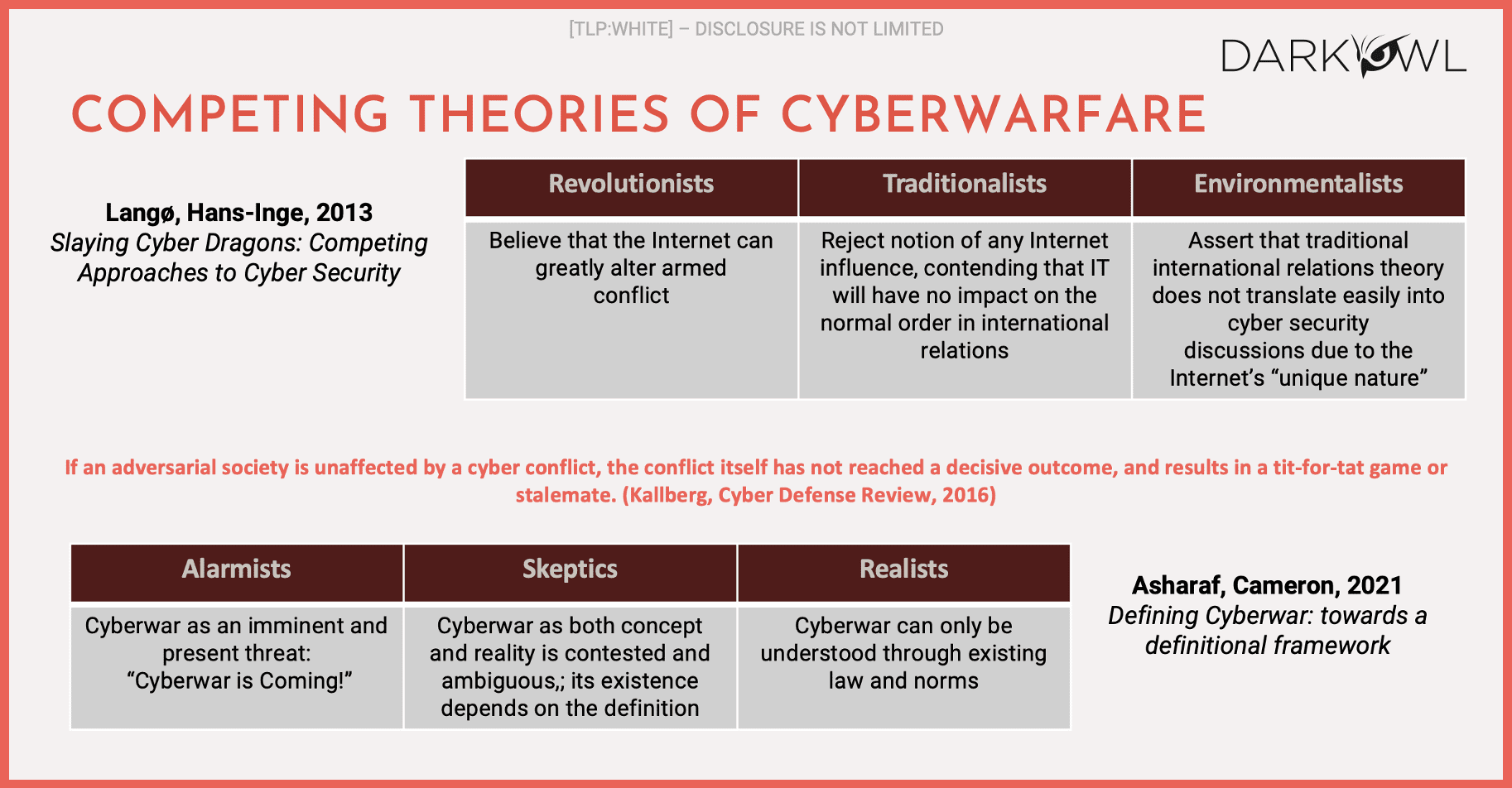

I want to just talk briefly about some of the competing academic theories of cyberwarfare.

Both of these boxes, the top and the bottom basically parallel each other, and they move from left to right. So on the left of each of the two boxes, the top is sort of a state of the art in 2013, the bottom is state of the art in 2021, and they basically parallel each other on the left. The revolutionists or the alarmists believe that cyberwarfare can change how we fight wars in general. They think it is a fundamental step change in how wars will be fought today and in the future. In the middle are the skeptics or the traditionalists who think it could be significant, but don’t think it will change how international order operates. And on the right, the environmentalists or the realists don’t really believe that it’s going to have a significant effect.

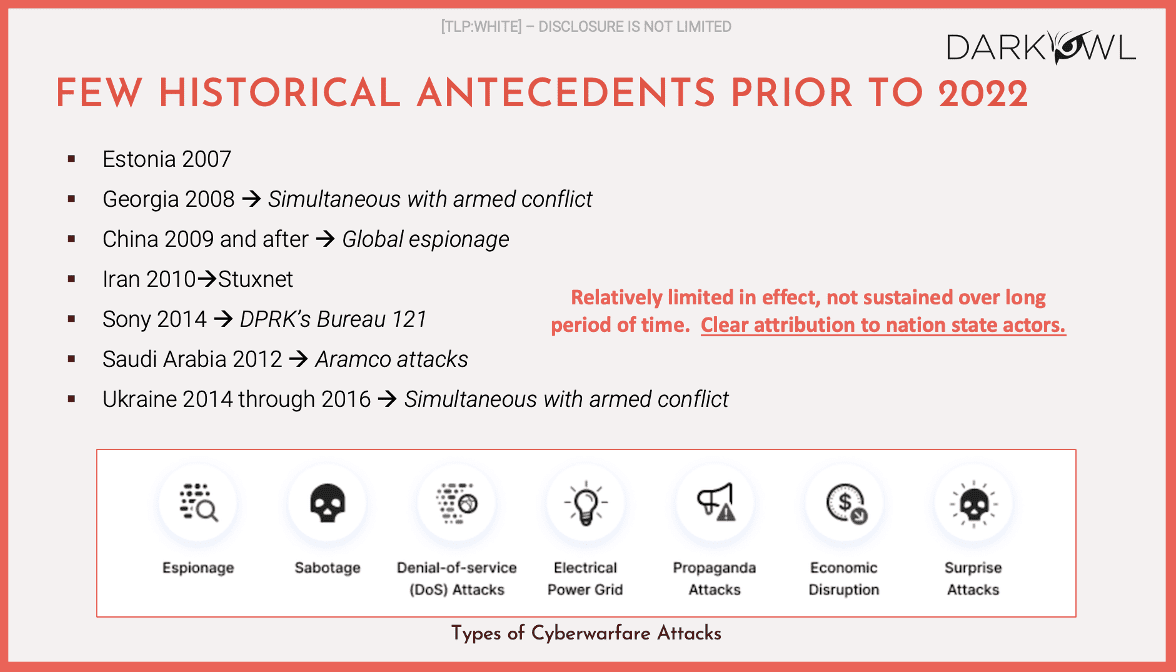

The problem with the competing academic theories of cyberwarfare is that none of these theories, at the time that they were formulated and articles were written about them, could reference a real, sustained cyberwar between two nation-states. These were theories, and they were based on the few historical antecedents prior to 2022. And in each of these historical antecedents… Estonia suffered a sustained multi-month attack by Russia in 2007, during a quick two month war in 2008 between Georgia and Russia, there was a cyberwar rage primarily from Russia to Georgia. China from 2009 onwards had a very significant global espionage effort underway. Iran, 2010, where the United States and Israel attacked the nuclear centrifuge facility in Frodos with the Stuxnet virus. In 2014, the North Koreans attacked Sony. In 2012, Saudi Arabia was attacked by Aramco, was attacked by Iran.

I would define all of these as largely skirmishes. Now, they were relatively limited. In effect, they were not sustained over a long period of time. But there was clear attribution to nation-state actors in each of the cases. The parties involved or the aggressor involved was a nation-state, and attribution was very clear. And in the Ukraine, from 2014 through through 2021, there was simultaneous with the armed conflict in the eastern side of the Ukraine, there were what I would call cyber skirmishes between Russia and the Ukraine. But in none of these cases did we see a sustained cyber hostility between two nation-states for longer than a couple of months. So the theories that I referenced on the prior slide had only these as the antecedents leading up to the current conflict between Russia and the Ukraine.

Dustin: I’m going to interrupt you there. We’ve had a couple of questions come in. The first one is: “Were all of these state to state attacks?”

Mark: Not all of these were state to state. In the case of the North Korean attack on Sony, that was a state on a private entity in the United States, it’s on the slide because we were able to make attribution to the aggressor, in this case North Korea being a nation-state. There are other examples. For example, it’s widely believed that the Russians hacked the International Anti-Doping Association and doxed a number of athletes in retaliation for Russian athletes. This is in the lead up to the Rio de Janeiro Olympic Games. That’s in response to Russian athletes being barred from representing Russia as a state in the Olympic Games. So that was another example of an attack on a private entity. But in all these other cases, these were state to state conflicts.

Dustin: “What impact did the CIA and NSA leaks of tools have on this?”

Mark: We at DarkOwl have written extensively about this. As recently as of three or four years ago, we published a paper on nation-state warfare in the darknet. Just by way of background, both the CIA and the NSA in the last four or five years have suffered significant leaks of their offensive weapons into the darknet and into the public. And our theory in looking at those leaks was that the widespread availability of the tools that were among the best tools that the NSA and the CIA had leveled the field in many respects between nation-states because a relatively small nation-state could go pick up those weapons and start to wage warfare against other countries and it didn’t necessarily elevate them to cyber superpower status. But it did have an effect. We don’t know whether any of these particular cyber skirmishes or cyberwars that took place or battles that took place used those weapons. Most of those I think both the CIA and the NSA leak took place after 2015. So only really the Russia-Ukraine war will probably have seen the use of any of those weapons, if at all.

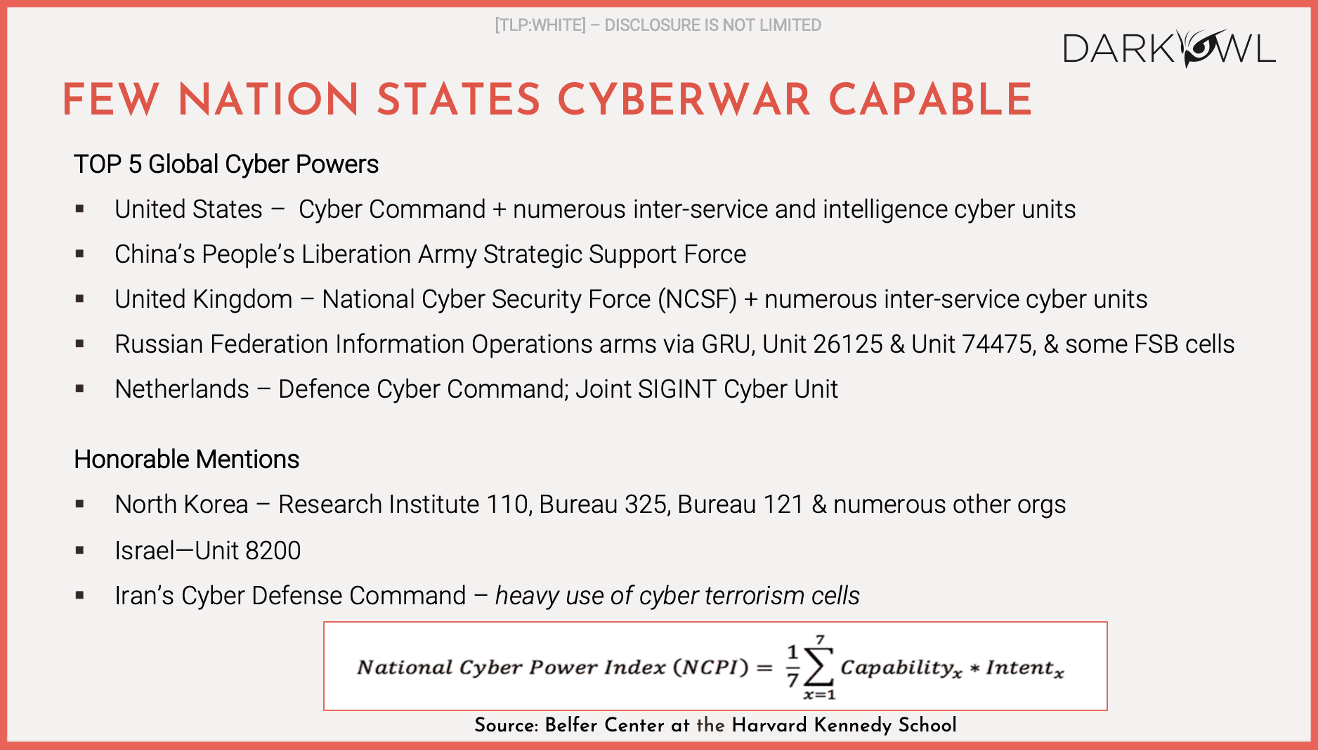

I wanted to throw this up because I talked about it just in lead up to our discussion, but the Belfast Center at the Harvard Kennedy School came up with a CyberPower index algorithm which is at the bottom of the page there and they rank the top five global cyberpowers as the US, China, UK, Russia and the Netherlands.

And perhaps there’s no surprise in that listing. The Netherlands are relatively small but a highly sophisticated country and they have made cybersecurity a significant part of their defense structure. I note here honorable mentions and I’ve talked about them before. North Korea, perhaps one of the lesser developed countries in Asia, is certainly a near cyber superpower, Israel, there’s a lot been written about Iran. None of them are particularly large countries. I think Iran’s population is verging on 60 million and is probably the largest, but the fact that they are able to achieve near superpower status is an indication that this is an area that they have significantly focused on.

So let’s talk about the Ukraine-Russia war and some of the observations that we have seen in the lead up to the Ukraine invasion in February, and by invasion I mean the invasion of the Russian troops, physical troops into Ukraine. We saw a significant amount of cyberattacks actually going back into the fall, but in mid-January there were significant cyberattacks against Ukrainian government services, government web-based services, there were a number of false flag operations attempting to implicate Poland in those attacks, which was interesting and we started to see wiper malware deployed in a variety of these attacks there were widespread leaks of Ukrainian citizen data there were a number of DDoS attacks that were mounted across Ukraine – there were a number of attacks on the Ukrainian financial sector.

Perhaps the most interesting thing in the lead up to the actual invasion was that there were six strains of wiper malware that were deployed and what we saw was a transition from traditional sources of attacks to wiper malware in the final weeks before the campaign and again many of these tried to implicate Poland as the source of the attacks but in reality Microsoft has done a pretty good robust study and identified six unique strains of wiper malware that were used and again.

Wiper malware goes onto a computer and wipes it – you don’t have any retrieval capability of the data that is kept on that. There was clearly a significant amount of cyberattacks that were waged in the months leading up to the actual war. We saw on the 24th of February the physical war started, Russia entered from the north, the south and the east into Ukraine and launched missiles at targets in the first 36 hours.

We’re now roughly six months out from the launch of that war so we’re now at a point where we can make some observations about what we have seen and start to make some hypotheses about how this war has been waged. A lot has been written about this but one of the most interesting and unanticipated things that we’ve seen in this war is that literally on day one the Ukrainian government requested help from the activists, the international activist community.

They formed the IT Army of the Ukraine on Telegram and put out a call for activists around the world to join them in attacking Russia from a cyber perspective. And the last time I checked, there were 300,000 or 400,000 followers on the IT Army of the Ukraine. By the way, that channel on Telegram is still very active on a daily and weekly basis. It provides targeting information to the activist community. As recently as yesterday, we saw new targeting information go up, targeting, I believe, Russian Financial targets in Russia. So what the Ukrainians were able to do, which I don’t think anyone anticipated, was suddenly galvanize an army of probably tens of thousands of activists around the world to start to attack Russian targets. And against the backdrop of a Ukrainian cyber armed, uniformed cyber force of probably hundreds or low single digit thousands, suddenly there were tens of thousands of people fighting on behalf of the Ukraine.

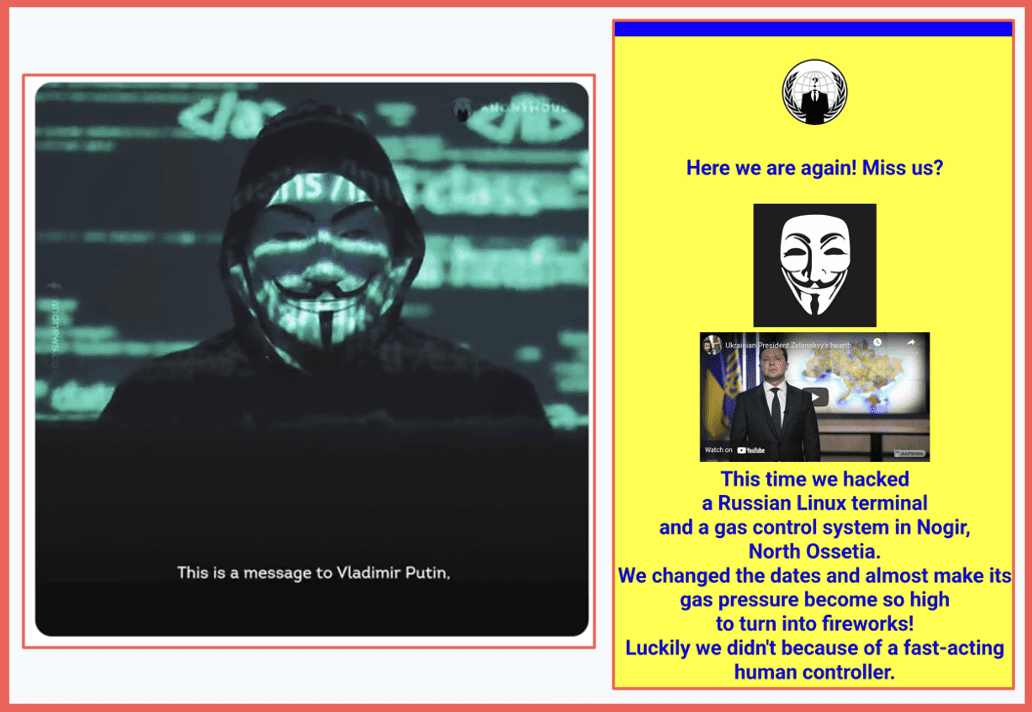

Day three of the war, Anonymous launched a campaign to attack Russia and the Belarus. And actually, Anonymous has since been joined by a number of other private actors who have stood up efforts to join the attacks in Russia. And by day five, we started to see a significant amount of data leak into the darknet from Russian targets, both civilian and military targets. In this case, we saw a leak of 60,000 government email addresses. There were immediately attacks on critical infrastructure suppliers: Gasprom, Foreigner, Gas, Mash Oil. A lot of them were hacked. In the first days of the war, it was very difficult as a Russian to get access to any government website and to get access to your bank. We saw tax of Russian state TV military communication leaks. We then started to see leaks of private information of Russian soldiers who were fighting in the Ukrainian battlefield, and they were doxed. And as I mentioned earlier, financial institutions were targeted. We continue to see daily DDoS campaigns. We’ve spoken to a couple of commercial entities in eastern Europe who are effectively offline from a commercial perspective because they’ve turned over their entire network to DDoSing Russian targets. So, you get a sense that overnight this was unanticipated. The Ukrainians were successful at galvanizing the international activist community to fight on their behalf, their offensive cyber capabilities increased by orders of magnitude.

Anonymous messages to Russia

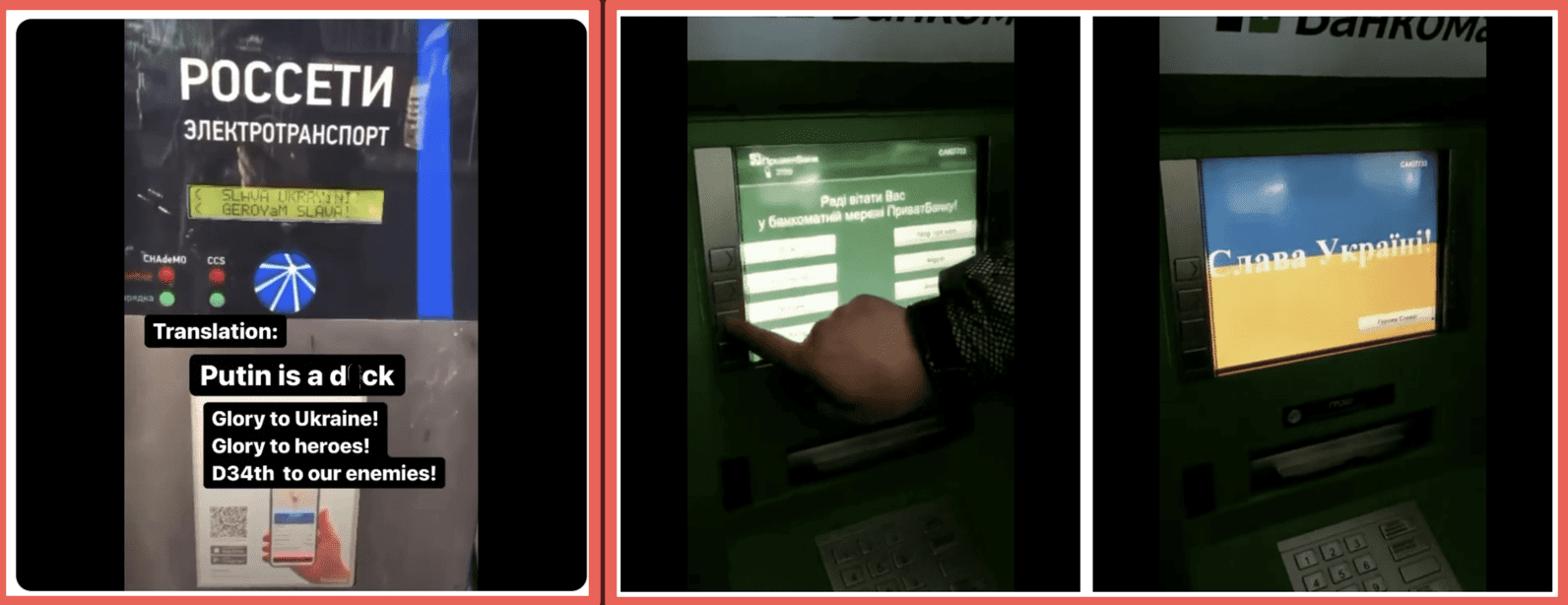

Quickly talking about some of the creative attack methods that were used, GhostSec carried out a printer hack. It turns out that Russian government printers are networked, and within a few weeks at the beginning of the war, GhostSec hacked that printer network and started spewing out inside Russian government facilities propaganda on behalf of the Ukrainians streetlight control systems were hacked. There were a variety of hacks of messaging systems used widely in Russia. We saw electrical vehicle charging stations hacked. We saw, both at the military and the civilian level, short band radio interception and direct trolling. And it turned out that the Russian military was using short band radio in the early stages of the war, and it didn’t take very long for that to be hacked as well. As I mentioned earlier, ATMs were hacked, radio and television channels were hacked. Flights were disrupted, food deliveries were dusted. So these were disruptions that occurred at the civilian level and at the military level in Russia in the early days of the war, but they were they were largely addressed by the Russians within hours.

And by the way, on the other opposite side, the same thing happened in the Ukraine. There were Russian attacks on Ukrainian ISPs, banks, government websites as well. But these don’t rise to the level of that definition that I gave you earlier in the webinar, which is Russia didn’t go dark and cold and stay that way.

Dustin: “Is the IT Army of Ukraine still active?”

Mark: Yes, it is. And I think I mentioned we actually monitor on a daily basis – it’s found in the darknet database yesterday. When I looked at it, I believe they were putting out targeting information for Russian financial targets. They’re still very active.

Dustin: “What are the long term implications of the IT Army for future cyberwarfare?”

Mark: Oh, that’s a great question. So the Director of the FBI has testified in front of Congress that the implications of something like the IT Army for future cyberwarfare are unknown, but they’re not positive. I think the words he used in his testimony were that if you green light 50,000 civilians around the world to attack another nation-state, it’s well within possibility that they could also attack the United States at some future date. And I think that in a lot of the cyberwarfare, that must have occurred at the federal government, at the military level in the United States, we may have anticipated five or ten or 20,000 Chinese or Russian soldiers cyber warriors attacking us. Once you start to increase that number by orders of magnitude, it changes the equation. So the long term implications are probably alarming and are poorly understood. But clearly, it’s a major issue for any country, by the way, not just the United States, any country that could face the wrath of people who have successfully attacked a nation-state in the past and know that they have the tools to do that.

Dustin: “Obviously, Russia must be monitoring these channels. Are some of these meant as deception or distraction efforts, while more specialized secret targets are addressed by specialized, more capable actors to take advantage of the chaos?”

Mark: Yes and yes. Clearly, Russia’s monitoring these channels, and my guess is, as soon as they see a bank and an IP range targeted, they’re trying to take whatever precautions they can. I don’t think it could be a deception effort by the Ukrainians to distract them from targets that are elsewhere. The reality, though, is that, especially in the context of a DDoS attack, the number of people participating matters. So even if they are deception efforts, they’re working. The actual attacks are working from what we can see. But that’s a great question as well. And I have no doubt, by the way, that the Ukrainians are not publicizing all of the attacks or all of the targets that they’re targeting.

These are some screenshots of some of the hacks of the electrical systems.

On the left is the EV electrical vehicle charging station, where the actual screen read obscenities about Putin. On the right are hacked ATMs. You’ll see the Ukrainian flag coming across the ATM on the right. One of the really concerning things, obviously, about cyberwarfare in general is the potential to attack critical infrastructure. And we have seen that in this war. We’ve seen a number of vulnerabilities. Exploited water and electricity facilities have been targeted. We haven’t seen a large scale shutdown of water and electrical facilities. They’ve been fairly narrowly time delimited. We have seen attacks on oil and gas refinement distribution centers, particularly near the Russia Ukraine border, and there have been a number of explosions. We don’t have direct attribution that those are caused by cyberattacks. We suspect they are. And in some of those cases, there were civilian casualties. Those have been perhaps the highest profile critical infrastructure attacks that we suspect were carried out by cyber warriors. We’ve seen satellites targeted. By the way, not only have the Russian satellites been targeted, but the Russians also targeted European satellites in the early stages of the war. We saw the Joint Institute for Nuclear Research was shut down for a number of days as a result of a DDoS attack. And then we’ve seen ISPs and other telecommunications providers. So again, we’ve seen these attacks occur.

We have seen some consequences, we suspect, from these attacks. What we have not seen is a sustained shutdown of any of these facilities as a result of these attacks. One of the real surprises for us was the ability of the Ukrainians to galvanize the international activist community and with unknown implications for the future of cyberwarfare. Another interesting and unanticipated consequence of this war has been that the criminals have fallen out with eachother.

Now, in the lead up to the war, we long suspected that many of the ransomware gangs and some of the other bad actors on the darknet were a combination of Russian and Ukrainians working together. And what we have seen since the beginning of the war is a very clear fallout between the Russians and the Ukrainians in the darknet, some of these gangs have split apart. Some of these gangs have clashed with each other. Where gangs had both Ukrainians and Russians in the gang and they split apart. Each side is leaking secrets into the darknet about the other side. And we’ve seen an unprecedented amount of data leaked into the darknet about the ransomware gangs, about their tactics, about the tools that they were using and how they were actually going about what they were doing. I mean, it’s been a treasure trove of information for us and for the industry to give people a sense of how much data has been leaked into the darknet. Both this type of data as well as just leaks as a result of a tax.

DarkOwl has been in existence just under five years. We’ve been collecting data continuously during that time. Since February of this year, the net size of our database and we archive all that data the net size of our database has increased by 20% in six months because so much data has been spilled out into the darknet. Some of these names may not mean anything to you, but these are among the major ransomware gangs leading up to the onset of the war. And what we have seen is that they have stayed split. They are still battling with each other. They’re still spilling eachother’s secrets into the darknet.

Dustin: “Have any of these attacks resulted in any significant physical damage?”

Mark: The only one that we’re aware of is, and we suspect because we can’t make direct attribution to a specific attack, are some of the explosions that have occurred in oil and gas distribution and refining facilities near the Ukraine Russia border. There doesn’t appear to be a physical reason for those explosions, which leaves cyber. And the Ukrainians, I think, in one or two cases, have taken credit for those explosions and credited their cyberattacks on that as well.

Dustin: “What is your assessment around why we have not seen sustained attacks against critical infrastructure?”

Mark: I’ll come on to that in the next couple of slides. Many of you will know that Belarus was used as a staging ground for the invasion of Ukraine from the north. In other words, Russian troops were in Belarus and moved from Belarus into the Ukraine, which then caused Belarus to become a target for the Ukrainians. And there were a number of attacks as well into the Ukraine. It was difficult, if not impossible, to buy a train ticket, and it severely disrupted the train system in Belarus in the early weeks of the war because such a successful cyberattack occurred. There were a number of attacks against banks, transportation, legal, military contractors. We saw a massive leak of data coming from the largest defense contractor in Belarus. There have been and again in the world, of criminal gangs fighting criminal gangs. GhostSec attacked a group called ghost rider who were aligned with the Russians. And GhostRider has remarkably retaliated with a really sophisticated phishing campaign. And their phishing campaign has targeted civilians in combat zones in the Ukraine with emails that come from Ukrainian government email addresses asking them to leave the area they’re in and congregate because of the war that’s being waged around them, and congregate in areas that have been subsequently been hit by shelling. That’s about as sophisticated phishing campaign as you can imagine. You’re geolocating the recipients, you’re sending them very official looking Ukrainian government emails. You’re sending them those emails at a time when they are hearing shelling or experiencing shelling in their neighborhood, and you’re moving them to areas that are more vulnerable. So that’s where the overlap occurs, between relatively harmless, between warfare that may or may not affect civilians to very directly affecting civilians. And it’s incredibly sophisticated what we’re seeing in terms of that unfolding.

And I’m going to come on to the question of why we’re not seeing more Russian attacks on critical infrastructure impact the US and western countries and companies in the region. So obviously Russia, the Ukraine, and Belarus are pretty well offline for any normal commercial activity and pretty well likely to be so for the indefinite future. We’ve seen that subsidiary and vendor risk in those countries and in the region, more broadly in the eastern European, risk has become extraordinarily high. And we have seen this among our own client base. We have seen vendors and contractors and subsidiaries for our own clients and their clients directly attacked, directly targeted, and in some cases compromised as a result of this cyberwar. So from an American or a western commercial perspective, you absolutely need to pay attention to any exposure that your organization may have in the region.

And let’s be clear, both Ukraine, Belarus, and Russia were all sources of relatively low cost and relatively sophisticated coding and computer science capabilities. And Ukraine in particular had tens of thousands of employees in Silicon Valley and western companies coding and working for them. Some of you may remember that in the early stages of the war, there was a terrible incident where a woman was taking her children and her husband to safety and was killed in a shelling in the street. She was the Marketing Director for a Silicon Valley company living in eastern Ukraine. That’s how close to the vein it is, particularly for the American tech sector. We did see critical infrastructure, as I’ve discussed, severely impaired. And our advice to companies that have any exposure in this region is to make an assessment and be extraordinarily cautious about how you move forward in the region.

This is the part of the answer to the question about attacks on critical systems. So, we have seen Russian attacks on western and Ukrainian critical infrastructure. The Russian attacks on Ukrainian critical infrastructure have largely received less publicity than the actual physical damage done by the war, which is occurring right there. So there hasn’t been a lot of publicity. I think there was some publicity about the fact that the main Ukrainian ISP was taken offline for a number of days by a Russian attack. It was subsequently restored. None of the power grids have gone off for more than a day. So I think those attacks have occurred. We have actually seen attacks on Western targets. The German wind turbine systems were knocked offline, there was a European satellite network that was targeted, we believe, by the Russians, Romanian gas stations were knocked offline. We’ve seen a fair level of increase in Chinese activity supporting Russia in this effort, which was a little bit of a surprise for us. And the FBI has already released indictments against Russian sponsored attacks on nuclear water facilities. We think in many respects, this is not the fullness of what Russia could do.

The retaliation by Russia against US and NATO or US and Western targets has been surprisingly ineffective. And our hypothesis is that there are a number of reasons for that. One is after Estonia and after the battles that we saw in the lead up to this war over the last decade, there has been billions of dollars invested in defensive cyber operations, and that is paid off well in this war. We also think the Russians are largely distracted by the attacks that are taking place against the targets in Russia and they’re preoccupying the cyber warriors. If you’re a Russian cyber warrior today, whether you’re a public or a private actor acting on behalf of the Russian state, right now, your predominant activity on a daily basis is going to be defensive in nature. We also have detected indication that in Russia there is a digital underground that opposes the Russian invasion of the Ukraine. And we’ve seen some targeting from inside Russia of attacks. And then there is a question of whether there is some lack of support in the Russian public. The public polls that we’ve seen indicate large spread support for the war by the Russian public. We don’t have any reason to doubt that. But as the war grinds on, and this is the same in any country, as the war grinds on and casualties mount, support tends to diminish. So I think that’s the answer. We’ve been surprised that the attacks from Russia have not been more sustained, more significant, and more serious, and that’s the best answer that we can come up with.

However, in the context of the first point that I made, which is our defensive posture, CISA early in the war, put out very specific guidance. Shields up. And here are things that you can do as a Western and American organization to better defend yourself against the prospect of a Russian attack, or any cyberattack for that matter. And these are obviously obvious to everybody who’s on this webinar. MFA, antivirus, anti-malware. Put up your spam filters, patch your software – how many times do we have to say that? And filter network traffic and monitor your logs, and knock on wood, that has had a significant effect today.

Dustin: “According to international law and the Geneva Convention rules, these private citizens attacking other nation-states organized under the Ukrainian government are legitimate military targets. What do you think will be the fallout or implications from this? If Russia has been able to successfully identify any of the members of the Ukrainian IG Army, do you think Russia or Russian aligned countries will try to arrest or conduct strikes on these people while they’re traveling?”

Mark: There’s a lot of good questions in there, and thank you for asking it. I’m not an expert on international law and the Geneva Convention, so I can’t actually address the first question about whether these are legitimate military targets. And my guess is that if Mark Turnage, sitting in Denver, Colorado, were to join the IT Army of the Ukraine and start to participate in attacks on Western on Russian targets somewhere in there, that would be a violation of US law, irrespective of the Geneva Convention or the rules of war. I may be violating US law, not that I don’t think the US is going to necessarily prosecute Mark Turnage for doing so. Certainly possible that they could do that. My guess is Interpol would not honor any international arrest warrant requests. Certainly, again, to use the example of me, if I were to travel to Russia, they could certainly arrest me and charge me with whatever they wanted. I think that one of the unknown implications of this war is the fact that we don’t know how this hacktivist army shapes up in future wars. But my guess is, to the extent that they are individual citizens and not uniform soldiers, they put themselves at some risk by participating in this. And, yes, they could be potentially arrested.

Dustin: “How does a commercial threat intel feed help me protect my organization from rogue IT armies?”

Mark: A lot of different ways. If I’m running a large Fortune 500 companies security and network and I have a robust threat intel feed I’m able to see whether my organization and its IP range is being actively discussed in targeting forums and in hacker networks that are adversarial to either my country or to my organization or these are just commercial ones so I can get a sort of pre warning on the fact that they are targeting my organization. I can get threat intel feeds on the nature of the vulnerabilities that are being used to exploit networks such as mine. So, I can draw a direct link between the software we use to protect our network and any known vulnerabilities of that particular software that are out in the darknet or out elsewhere for sale or being actively used. And for the most sophisticated of those organizations, they’re able to take some proactive steps to avoid attacking. So I would see that a dedicated, robust threat intel feed that encompasses both the darknet and social media is critical to any security posture for a large organization and if nothing else, this war has proven that very robustly.

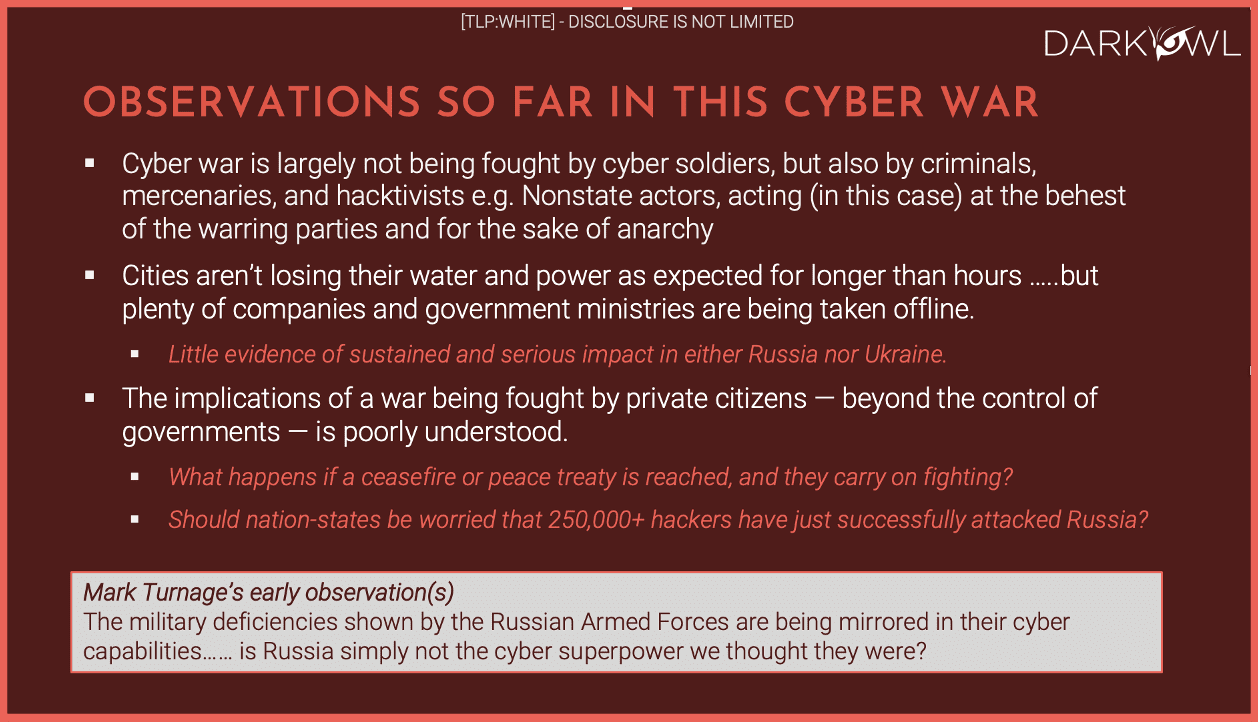

Let’s talk about some of the observations so far in this war. As I mentioned, this war is largely not being fought by cyber soldiers but by criminals, mercenaries and activists and non-state actors who are acting at the behest of the warring parties. It’s an unknown, crazy world we’re walking into, to be honest. This was not anticipated by anybody and my guess is that in the war games that we conducted leading up to the Russia Ukraine war, this fact did not feature highly, if at all. As I’ve said, cities aren’t losing their power and water for longer than a few hours. Plenty of companies and government ministries are being taken offline, but again for days, not even weeks and there’s little evidence of sustained serious impact in Russia or the Ukraine. Again, the bulk of the focus in the Ukraine is on the physical damage that’s being done that’s being rotten on the country.

And then in answer to the question that came in earlier, the implications of war being fought by private citizens beyond the control of governments is really poorly understood. And I throw down here a couple of hypothetical questions of what happens is if a ceasefire or a peace treaty is reached between the Ukraine and Russia and the private warriors just carry on, what are the implications of that?

They’re profound, actually and this echoes the FBI director – should nation-states be worried that somewhere we don’t know if it’s 250,000 plus hackers, 50,000 hackers, but tens of thousands of hackers have successfully attacked Russia? At the bottom I put one of my early observations in the actual physical war that has been fought between Russia and the Ukraine there have been a number of deficiencies in the Russian armed forces that have been identified and they’ve been surprising, to be honest. Some of them have to do with supply chain and how the Russian armed forces support its troops in the field. Some of them have to do with the maintenance of Russian military equipment and so on. I’m wondering if there’s a similar deficiency that we’ve seen in the Russian cyber capabilities. Are they simply not the superpower we thought they are? The alternative, the flip side of that coin is they could be holding back. They could have an arsenal of cyber weapons that they’ve not deployed and not used. But it could very well be that to the extent that the Emperor has no clothes on their physical military capabilities, that the same is true in the cybersphere.

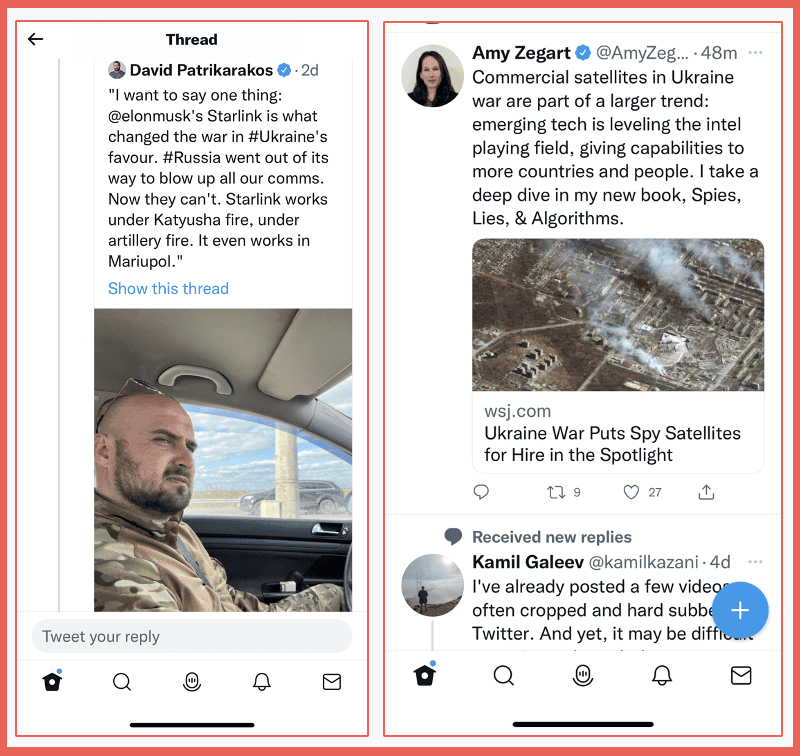

Observations on the privatization of warfare – this is another surprise and it doesn’t really address the cyberwarfare capability, the cyber implications. But this is a war where private actors on both sides are playing a significant, major role in the attacks in the war, and I mean both the cyberwar and the physical warfare. So as we’ve talked about, private hackers are waging a war on behalf of Ukraine, Russia. That’s been a real surprise. If not 100% of the military communication by the Ukrainians is done by Starlink. Early in the war the Russians were successfully took offline the Ukrainian military communication system. Within days, Elon Musk and SpaceX had launched satellites over Ukraine. And today the bulk of the communications that the Ukrainian military uses is provided by a private American enterprise. Now let that sink in. That’s a commercial enterprise that is doing that. Some of the best reporting on the war has been by OS analysts, not by US government analysts who have been using commercial satellite imagery that has been widely available since the beginning of the war. The coverage, particularly many of them have posted their analyses on Twitter have been very good.

The Western sanctions that have been imposed on Russia and its allies in connection with this war are being privately enforced by banks and companies. Those are private enforcement capabilities efforts. I would point all of you to bellingcat as a great OSINT source using open source tools that are available on the Russian side. The Wagner Group is heavily involved. It’s a private mercenary enterprise. It’s heavily involved in the war in Eastern Ukraine up to and including flying fighter jets for the Russians. And obviously there’s a fair amount of pressure on companies continuing to do business with Russia.

We have made the observation that private hackers are engaged in this war. It’s not just private hackers. Right through the war on both sides, private actors are playing a very significant role in the waging of this war. What are the implications for the post war darknet? DarkOwl is a darknet intelligence company. We gather data continuously from the darknet and we provide that to our clients around the world as a threat intel feed or as a source of information so we see a lot of this unfolding, particularly in the darknet and what I call a chaotic and often unruly environment in the darknet, just became even more chaotic and risky. When you start to see major criminal gangs in the darknet start to fight each other and leak each other’s information into the darknet. But it’s a golden source of information for us and for our clients. But it’s also just an indication of just how anarchic that capability has become. These criminals will continue to turn on each other, but that’s not going to last forever, and we don’t know how this is ultimately going to shake out. Ransomware has been a big focus of criminal activity in the darknet. We expect that there will be a shift that that will continue to be the case. But we’ll see more wiper malware deployed.

So the consequences, again, for a US Hospital that’s subject to a ransomware attack of not paying a ransom, may be even worse by not paying the ransom if they don’t have a backup and they don’t have other capabilities to restore their network. If the criminals on the other side of that effort choose to deploy wiper malware, you may lose those, particularly if you don’t have backup. You may lose those medical records forever. Again, very sophisticated malware targeting for industrial control systems that we’ve seen.

We’ve seen an increase in awareness about what the darknet is and how it can be used. Propaganda and disinformation – I’ve spent relatively little time in this presentation talking about propaganda and disinformation, primarily because most of those efforts are in social media, not so much in the darknet, although we do see it occurring in the darknet. And as I said earlier, the hacktivist movement has been unleashed.

Here are some unanswered questions and I think some of the questions that we’ve had during the course of this webinar are addressing some of these:

- How do the laws of war apply to cyberwarfare both in the decision to go to war and in the decision to wage the war and how you wage that war? The implications of it are very poorly understood. The attribution error issues, frankly, scared me to death.

- How does one deescalate against cyberattacks that are coming in that you think but don’t know for sure are coming from an adversary? Where’s the safety valve in all of this? In physical warfare? I can see that your planes are coming to attack my targets. I can see that you’re shelling me from behind your lines in cyberwarfare. It’s a far messier calculation and the implications of that are frankly, frightening.

- What are the implications with the appearance of non-state actors on the stage? We don’t know. Will cyber become strategically decisive in a war? It has not been strategically decisive in the Ukraine Russia war, although it’s been a significant factor, but it’s not been strategically decisive. And where is the line between cyber terrorism, cyber criminal activity and cyber hacktivism on the battlefield to be determined going forward.

Thank you very much for joining us today.

Curious about something you read? Interested in learning more? Contact us to find out how darknet data applies to your use case.

Explore the Products

See why DarkOwl is the Leader in Darknet Data

Products

Services

Use Cases